Big questions remain. The numbers add up to trouble for the oceans, wildlife, and us, but scientists are struggling to understand how. The numbers are staggering: There are 5 billion pieces of plastic debris in the ocean. Of that mass, 269,000 tons float on the surface, while some four billion plastic microfibers per square kilometer litter the deep sea.

The numbers are staggering: Of that mass, 269,000 tons float on the surface, while some four billion plastic microfibers per square kilometer litter the deep sea.

Scientists call these statistics the “wow factor” of ocean trash. The tallies, published last year in three separate scientific papers, are useful in red-flagging the scope of the problem for the public. But beyond the shock value, just how does adding up those rice-size fragments of plastic help solve the problem?

Although scientists have known for decades about the accumulating mass of ocean debris and its deadly consequences for seabirds, fish, and marine animals, the science of sea trash is young and full of as-yet-unsolved mysteries. Almost nothing was known about the amount of plastic in remote regions of the Southern Hemisphere, for example, until last year because few had ever traveled there to collect samples.

“The first piece is to understand where it is,” says Kara Lavender Law, an oceanographer at the Sea Education Association in Woods Hole, Massachusetts.

Indeed, until scientists learn more about where ocean trash is, how densely plastic accumulates in different ocean ecosystems, and how it degrades, they can’t really calculate the damage it’s causing. There are still big, basic questions: As it degrades, do plastic toxins seep into the marine environment? If so, how and in what amounts?

And though scientists know a great deal about the damage to marine life caused by large pieces of plastic, the potential harm caused by microplastics is less clear. What effect do they have on fish that consume them?

“The greater the concentration, the greater the potential risk for exposure,” says Richard Thompson, a biologist at Plymouth University in England, whose study released last month identified microfibers widely disseminated throughout the deep ocean. “If we are missing a major sink where there are major concentrations of plastic, we might not be learning how harmful plastics are.”

The most recent counts add significantly to the knowledge base, yet even those big numbers are a fraction of the plastic that flows into the oceans every year. Where’s the rest of it? It’s another mystery.

We are dealing with pieces from hundreds of meters down to microns in size,” Thompson says. “It is incredibly challenging to monitor.”

Ocean trash is counted in three ways: through beach surveys, computer models based on samples collected at sea, and estimates of the amount of trash entering the oceans.

The most recent counts involved computer modeling based on samples taken at sea. The models may not account for all of the trash, scientists say; nonetheless, the new numbers are helping address some of the questions.

The process of collecting and counting is meticulous, time-consuming work. It took Marcus Eriksen, co-founder of the 5 Gyres Institute, a nonprofit ocean advocacy group, more than four years, using samples gathered from 24 survey trips, to come up with his estimate that 5.25 trillion pieces of debris float on the surface.

In the course of his expeditions, Eriksen collected everything from plastic candy wrappers to giant balls of fish netting. One massive ball of netting, found midway across the Pacific, contained 89 different kinds of net and line, all wrapped around a tiny, two-inch-high teddy bear wearing a sorcerer’s cap at the center.

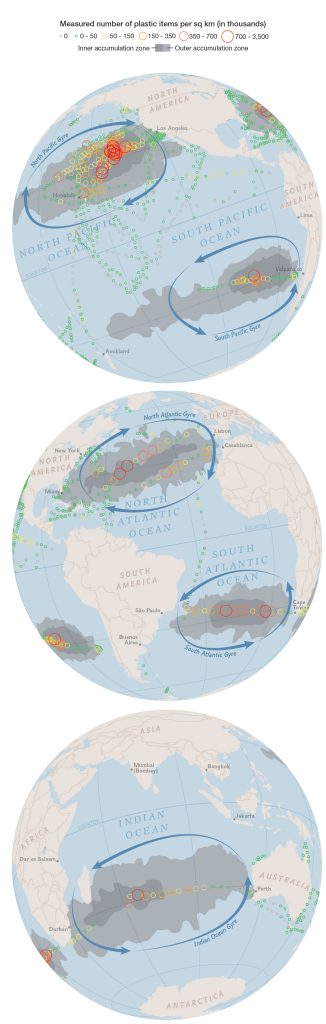

He says his research has helped fill in the outlines of the life cycle of ocean plastic. It tends to collect in the world’s five large gyres, which are large systems of spiraling currents. Then, as the plastic degrades into fragments, it falls into deeper water, where currents carry it to remote parts of the globe.

“These fragments are anywhere on the planet at this point,” he says. “We’re finding them everywhere.”

Eriksen’s findings agree with those of a Spanish scientist, Andres Cozar Cabañas, a researcher at the University of Cadiz, in Spain, who published the first global map of floating ocean debris last July. Their estimates are strikingly similar.

“We now have two estimates of what is floating, and they are almost identical,” says Lavender Law. “They used different data sets and different methodology and came up with the same number. That gives us confidence we’re in the right ballpark.”

Another way of coming up with the numbers is to make crude guesses based on manufacturing statistics. Says Jenna Jambeck, a University of Georgia environmental engineer who is completing a worldwide calculation of garbage collected in coastal countries: “If you have 200 million tons produced every year, researchers will arbitrarily estimate that 10 percent goes into the oceans.”

Sort Out the Rubbish

It’s not too difficult to surmise why so much plastic ends up in the ocean. The Plastic Disclosure Project, a project run by Hong Kong-based advocacy group Ocean Recovery Alliance, estimates that 33 percent of plastic manufactured worldwide is used once, then discarded. To compound matters, 85 percent of the world’s plastic is not recycled.

Despite the magnitude of the numbers, Peter Ryan, a zoologist at the University of Cape Town, South Africa, who is writing a book tracing the evolution of marine debris research, says the problem can be solved.

“Marine debris, unlike global warming, should be an easy thing to deal with,” he says. “We have to sort out what to do with our rubbish.”

Ryan began tracking debris 30 years ago, after a colleague suggested he should study seabirds that were eating floating plastic pellets, then commonly used in manufacturing and found in harbors and other waterways. Improvements to shipping reduced pellet spillage.

“If you go to the beach today, you struggle to find one,” he says. “We can show that in every study that looks at the North Atlantic that the amount of pellets [ingested by] seabirds has decreased over the last two decades.”

But gains on that front have given way to losses in others, as microplastics have become more prevalent.

Emily Penn skippers the 72-foot, steel-hulled Sea Dragon, which carries scientists, including Eriksen and Jambeck, on sea trash sampling surveys. She expertly handles the nets trawled behind the vessel and knows what to expect. Nevertheless, she is still surprised and dismayed by the volume of trash.

“The thing that shocks me every time is the fact that the ocean looks like it is clear blue water,” she says. “And then … we pull out that sock at the end of the net and find it’s full of thousands of fragments of plastic.”